From the Womb: The Early Years

1972-1976

By Rowena A. Rivera

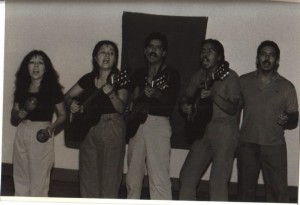

To think of Su Teatro is to reflect up on the idealistic, activist, and very creative years of the Denver/Boulder Chicano Movement of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. For those of us, both Chicano students and professors, who were deeply involved in activities such as Rodolfo (Corky) Gonzales’ political movement, César Chávez’s Farmworker marches, Magdaleno Avila’s efforts to improve the living and working conditions of Colorado farmworkers, Chicana activism, the Colorado Penitentiary Reform Movement, and in many other Mexican-American political, social, and educational projects, those difficult but exhilarating years marked and defined us for the rest of our lives. Some of these organization and activities, while no longer in their most vigorous state, still remain in this area some no longer exist. And only a very few have not only survived, but have gone through diverse social and political changes, have adjusted to Chicano generation, and in spite of different mental attitudes, are more vigorous and more vital than before. The best example of this is Su Teatro, who now leads the way in Colorado Chicano theatrer, but also in Mexican American theater throughout the United States. It was, therefore, with great emotion and with many pleasurable memories that suddenly came to the forefront, that I accepted the invation to write an essay describing how I founded Su Teatro in 1972 at what was then known as the University of Colorado, Denver Center. At that time I taught Spanish Language and Latin American literature course at the University of Colorado, Boulder. And since there were very few us Chicanos who taught in Colorado Universities, and across the nation as well, those who were on the university level worked together in many of these Chicano activities. And that is why Macela Trujillo, the director, and Donald Urioste, the assistant director, of the UCDC Mexican-American Educational Program, asked me to come to their Denver program and teach some courses for them. They indicated, however that they wanted me to teach remedial English reading and writing courses, the basic course that was then taught to the many Chicanos, who, under the brilliant political strategies of Salvador Ramiréz, a sociology professor at the Boulder campus were being admitted into the university system. In those early years of the Colorado Chicano movement, it was not usual for us to teach disciplines other than our own. We simply had to read extensively, acquaint ourselves to the best of our ability with a new field, and then teach classes in Chicano history, literature, sociology, politics, and whatever else was needed by the Chicano students. I decided to accept Marcela and Don’s offer to teach one course of their program, but confessed that I didn’t like the title of the class. It seemed that “remedial anything” already embodied the idea of deficiency and might bring about inevitable failure. I felt I could fulfill the same objective from a different and more enjoyable perspective; say through a class in theater in which students would be asked to write and read their original scripts. Both immediately embraced the idea, but, of course, anticipated a negative response form the administration. They began a long series of meetings with their deans, and ultimately, it was through Marcela and Don’s persuasiveness and faith in this very different course, that we were allowed to teach teatro at the Denver Center. My first class was composed of students who were very interested but who had little familiarity with drama. In fact, many had never seen a play before. We spent the first session speaking of the social, political, and artistic implications of Luis Valdez’ Teatro Campesino, of possible topics from their own Colorado context that could be brought to the stage, and of their own original writing and reading of scripts to be performed in class. It was important, we agreed, that these plays reflect their own lives and their identity as Chicanos. From these discussions emerged such themes as problems in school, police brutality, broken families, foster care, street violence and many others. But we also discussed inherited Chicano mythologies/artistic plots, such as though found in folklore, in traditional legends, and cuentos (short stories), in ballads or corridos, and many other Mexican-American musical genres. And fortunately, we had within our group much needed guitarists, singers, and even a harmonica player to create music for our dramatic presentation. Our talks then centered on the objectives of this theatrical group. Was it only for us or was it also for our community? The students felt that since their dramatic works were being written by Chicanos to be performed in their own community, their efforts would then be their artistic contribution to their Mexican-American social group in Colorado. Diana DeHerrera suggested a name that meant that it be a theatre for the people, meaning our audiences. I then suggested the name Su Teatro (Your Theater), and that name was accepted. We began with the reading of two of Luis Valdez’ Actos, “No saco nada de la esquela” and “Los vedidos,” two plays in which the students refined basic techniques such as theatrical body movements, timing, improvisational commentary and, especially, humor which underscored definite social protest. They had very little difficulty with that since these were elements they already employed in their own verbal communication. We had neither props nor stage and absolutely no money, so our stage was anywhere, our props were imaginary and our stage costumes were everyday apparel. For special effects, we used old clothing donated by the Denver Goodwill stores. Out first performance was to an enthusiastic student body in the lobby of the Denver Center. We were subsequently invited to present our plays at the other Denver universities and at Chicano community centers. And recalling that Luis Valdez always reminded his actors that “Si la gente no va al teatro, que vaya el teatro a la gente.” (“If the community does not go to the theater, then the theater goes to the community”), we performed our plays during lunch time in downtown Denver parks, sidewalks, streets, and especially, in Larimer Street, which, at the time, was considered a violent and dangerous area. After this initial stage, students then began to write their own scripts which they read to each other for comments, suggestions, and approval and to create improvisational theater, which, after the performances, was written up by the author or co-authors of those dramatic works. Su Teatro soon became known throughout the Denver area, and thereafter we were invited to perform at other sites, such as the Colorado State Penitentiary in Canyon City, in Boulder and other nearby communities. Everywhere we performed, we were received with enormous enthusiasm; audiences readily responded to the student/actors’ humor, to their intelligence, to their exceptional talent and creative imagination. I believe that, for many of these 1971 students, this experience with theater was the first time they felt a sense of recognition, of achievement, and deep pride in their culture and identity as Chicanos. They worked hard reading, writing, memorizing, rehearsing and exploring their artistic potential as individuals and as a group. This essay, therefore, would be incomplete without acknowledging those first original actors. The group included among others, Camelita Muñiz, Rocky Hernández, Margatrito Berzoza, Arturo Valdez, Ruth Rivera, Diana DeHerrera-Garcia, Alice Avila Lucero, Yvonne Sanchez, Eva Aragon, Alex Campos, Kris Montoya, Raymond Kinoshita, Dalia Longoria, Pauline Lopez, Chris Navarro and Eddie Hernández. And later, Anthony Gacía, who through his untiring efforts and his long-time commitment to Chicano theater, has not only kept Su Teatro alive, but has been a guiding force in its extraordinary revolution. He, along with Debra Gallegos, Yolanda Ortega-Ericksen, Sherry Coca-Candelaria, Rudy Bustos, and Angel Mendez-Soto, continued with this tradition of taking Teatro to the people. Today we see young people such as José Mercado and others who are still dedicating their time and determined endeavors to the maintenance of this theatrical group, they deserve our admiration and deep gratitude.Rowena Rivera is now living in Albuquerque, where she is an

author and educator.