About The St. Cajetan’s Reunification Project

Every December, Su Teatro organizes a community-building effort known as the St. Cajetan’s Reunification Project. The project is designed to commemorate the tight knit Auraria community that was displaced when the Auraria campus was built in 1972, to offer healing to community members and to bring together artists, community member, students and faculty at the Auraria Higher Education Center.

In conjunction with the project, over 18 years Su Teatro has performed works such as the nationally recognized production

The Westside Oratorio (made possible through a grant from the American Composer’s Forum,

Continental Harmony program);

Las Nuevas Tamaleras by Alicia Mena); Su Teatro original plays by resident playwright Anthony J. Garcia, including

The Miracle at Tepeyac, El Corrido del Barrio, and

Joaquin’s Christmas, and now, El Teatro Campesino’s

La Pastorela.

The St. Cajetan’s Reunification Project is a symbolic gesture, commemorating the neighborhood that was sacrificed in order to build the Auraria Higher Education Center in 1972, but also honors the sacrifices of countless generations of Chicanos, beginning even before the Conquest.

Since the depopulation of the St. Cajetan’s neighborhood in the 1960s and the construction of the Auraria Higher Education Center, the near Westside community has continued to lose territory, homes and residents.

El Centro Su Teatro Executive Artistic Director, Anthony J. Garcia, as well as countless El Centro Su Teatro supporters (including Magdalena Gallegos, who edited a tribute to the neighborhood,

Auraria Remembered; former

board member Santos Blan, and UCD Theatre Chair Laura Cuetara) grew up in the Ninth St. neighborhood surrounding St. Cajetan’s Church. Garcia writes:

The “West Side” called Auraria by the city consisted of Victorian houses owned by the families living in them. The houses are still standing but the tenants are gone, replaced by offices for the Auraria Higher Education Center. They stand as a monument to the concept of property value over human values. There are ghosts that haunt Ninth St. Park which runs through the center of “Auraria.” They are the echoes of the Torres, Deleon, Rodriguez and Gonzaled families who gave birth, celebrated weddings and shared sorrows as all communities do.

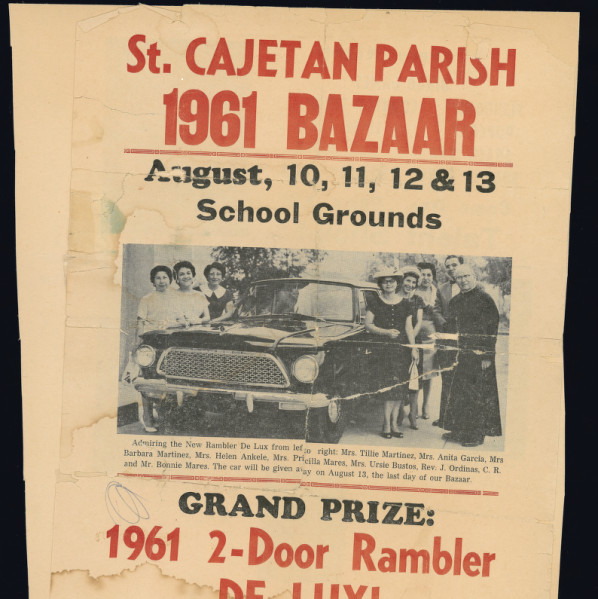

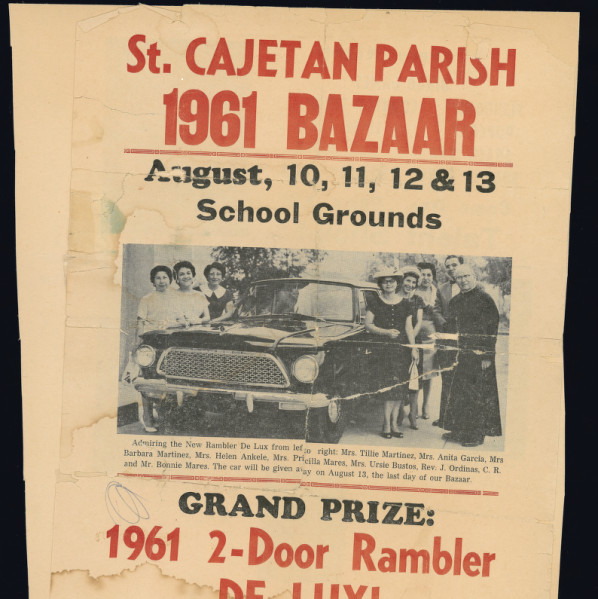

In 1926, St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church was erected at Ninth and Lawrence streets. According to Magdalena Gallegos, whose family had lived in the neighborhood for four generations, the lives of residents revolved around their church. Garcia notes, St. Cajetan’s was “the first church for the Spanish speaking in the city. Aside from weddings, baptisms and funerals, the Church operated an elementary school, a credit union, and fraternal and religious organization.”

Auraria was a tightly bonded community where children were encouraged to explore their talents. Before Garcia or Gallegos, the neighborhood produced Maria Gonzales-Zimmerman, whose family left Mexico during the Revolution, moved to Denver, and opened the Casa Mayan restaurant. Zimmerman attended the Lamont School of Music as a teenager, and performed as an opera singer in New York City. According to Magdalena Gallegos, the sisters at St. Cajetan’s Church played rhumbas and sambas on the pipe organ , for interested young students. “They grew their own (talent)” says Gallegos.

The neighborhood experienced tumult as well, including attempts to anglicize the Catholic Church in the 1950s. “Overnight, Father Juan Ordonez, became Father John, Sra. Maria, became Sra. Mary, says Gallegos. The closing of inner city community schools, including Annunciation, St. Joseph’s and Cathedral High School, eroded community and decreased the quality of education available to Mexican-Americans, Gallegos believes. “We begged them, please don’t close our schools.”

In the late 1960s, the City of Denver began examining plans to relocate students in order to build a campus near the Tivoli Brewery. Residents learned of the relocation through leaflets distributed by the city, describing the proposal. According to Gallegos, “The residents did not want to move and one hundred and fifty-five families filed lawsuits. Governor John Love then created the Auraria Higher Education Board to act as both land lord and moderator. In 1969 the city called a special bond election to secure funds for the project (Gallegos, 1991 p. 1).

According to Gallegos, Father Pete Garcia, Assistant Pastor of St. Cajetan’s Church, helped to organize the Auraria Residents Organization (ARO Inc.) to organize opposition to the bond election. In spite of these efforts, the organization was defeated, possibly due to a letter from Archbishop James Casey, urging Catholics to vote for the bond issue (Gallegos, 1991, p.1)

For residents of the Ninth St. neighborhood, life was forever changed. When the neighborhood was targeted for demolition, the local newspapers described the neighborhood as dilapidated and the residents as uneducated and poor. According to Gallegos, “it really hurt” that the city justified its actions by objectifying residents and minimizing the value of a community they loved, and relationships with neighbors that they cherished.

In his play,

El Corrido del Barrio, Garcia celebrates the stories of residents: a scary ride from Hotchkiss to Denver in a Model-T; boys watching the cars of white diners at The Casa Mayan restaurant; and hanging out at Sammy K’s bar. Garcia also chronicles the sacrifices of residents, who not only gave up their neighborhood, but relinquished their sons to racist cops and the Viet Nam War; but he ties together their struggle with the sweetness of everyday life: women cooking and doing laundry together, kids singing and playing games, and young lovers courting. Garcia highlights historical continuity – the cycle of death and renewal – accentuated by Conquest and migration.